Introduction of 141 IPC

IPC Section 141 defines unlawful assembly as a group of five or more people who come together with a common purpose to commit an illegal act. If their objective involves using force, violence, or resistance against the law, the assembly is considered unlawful. Even a gathering that starts legally can become unlawful if its members decide to commit a crime or disrupt public order. This section helps in maintaining peace and preventing riots or violent protests.

- Introduction of 141 IPC

- What is IPC Section 141 ?

- Section 141 IPC in Simple Points

- IPC Section 141 Overview

- 2. Intimidating the Government or Public Servants

- 3. Resisting Law Enforcement or Legal Process

- 4. Committing Mischief or Criminal Trespass

- 5. Forcing Someone to Give Up Their Rights

- 6. Forcing Someone to Do Something Against Their Will

- 7. When a Lawful Assembly Becomes Unlawful

- 8. Minimum Number of People Required

- 9. Role of Common Object in Unlawful Assembly

- 10. Legal Consequences of Unlawful Assembly

- IPC 141 Punishment

- 141 IPC bailable or not ?

- Section 141 IPC case laws

- Section 141 IPC in short information

- 141 IPC FAQs

- If you need support with court proceedings or any other legal matters, don’t hesitate to reach out for assistance.

What is IPC Section 141 ?

An unlawful assembly is a group of five or more people who gather with a common illegal objective, such as:

- Using criminal force to influence the government or public officials

- Resisting the execution of any law or legal order

- Committing mischief, trespassing, or other offenses

- Forcefully taking over property, land, or public rights

- Compelling someone to act against their legal rights through threats or violence

Even if a group starts as lawful, it can become unlawful if its purpose changes to an illegal act.

Section 141 IPC in Simple Points

1. Minimum Five People Required

An assembly must have at least five members to be considered unlawful under IPC 141. If fewer than five people gather, this law does not apply. However, other laws, like rioting or assault, may apply if they commit a crime.

For example, if four people attack a shop, they may be charged with theft or vandalism but not unlawful assembly. But if five or more people attack together with a common goal, they are charged under IPC 141.

2. Common Unlawful Purpose

For an assembly to be unlawful, its members must share a common goal that involves breaking the law. It does not matter whether all members actively participate—if they support the illegal objective, they are guilty.

For instance, if a group gathers to block a road and forcefully stop traffic, it is an unlawful assembly. Even if some members do not throw stones or attack vehicles, they are still guilty because they are part of the group.

3. Force or Violence Against Government or Public Servants

If an assembly is formed to threaten or attack a government official, police officer, or any public servant, it is considered unlawful. Using force, intimidation, or violence to influence the government or stop legal action is illegal.

For example, if a group of people surrounds a police station and threatens officers to release a criminal, they are committing an unlawful assembly under IPC 141. Similarly, if protestors use criminal force to make a judge change a court decision, they can be punished under this section.

4. Using Force to Take Someone’s Property or Rights

If a group gathers to forcefully take land, block a road, stop water supply, or remove someone from a place, it is unlawful. The law protects public and private property from being taken over by violent groups.

For example, if five people enter a farmer’s land and claim it belongs to them, stopping him from farming, it is an unlawful assembly. Similarly, if a group blocks access to a well and stops others from using water, they can be punished under IPC 141.

5. When a Peaceful Gathering Turns Unlawful

A lawful gathering can become unlawful if its purpose changes to committing a crime. Even if a protest starts peacefully, but later members decide to damage property, attack people, or break the law, it becomes an unlawful assembly.

For example, if students protest peacefully for lower fees, it is legal. But if they start burning college buildings, attacking staff, or damaging vehicles, it becomes an unlawful assembly under IPC 141.

IPC Section 141 Overview

IPC Section 141 defines unlawful assembly as a gathering of five or more people who share a common unlawful objective. The objective could be to resist the law, threaten public order, use force against someone, or disturb the peace. Even if a group starts as a lawful gathering, it can become unlawful if its members engage in illegal activities. Below are 10 detailed key points explaining this law in simple, clear language.

Key-Points

1. Definition of Unlawful Assembly

An unlawful assembly is a group of five or more persons gathered for an illegal purpose. The law does not criminalize large gatherings, but it becomes unlawful when the members share a common goal to break the law or cause harm. The presence of five members is essential—if the number is less, IPC 141 does not apply.

For example, if five people gather to protest peacefully, it is legal. But if they gather to vandalize a government office, it becomes unlawful. Similarly, a crowd at a public event is not unlawful, but if they start attacking people, they become an unlawful assembly.

2. Intimidating the Government or Public Servants

If a group gathers to threaten, intimidate, or use force against the Central or State Government, Parliament, State Legislature, or a public servant, it is an unlawful assembly. The intention can be to pressure officials, stop them from performing duties, or change government policies through fear.

For example, if a mob enters a government office and threatens officers to change a law, it is an unlawful assembly. Similarly, if people block a judge’s house and force him to decide a case in their favor, they can be charged under IPC 141.

3. Resisting Law Enforcement or Legal Process

An assembly is unlawful if it is formed to resist arrest, stop police action, or prevent a court order from being executed. This means stopping police officers from doing their duty, blocking legal notices, or protecting someone from lawful arrest.

For instance, if police come to seize property under a court order and a crowd gathers to stop them by force, it is an unlawful assembly. Similarly, if people block a road to prevent police from arresting a criminal, they are also part of an unlawful assembly.

4. Committing Mischief or Criminal Trespass

An assembly is considered unlawful if its objective is to destroy property, damage vehicles, enter private property illegally, or commit any offense like theft or arson. Mischief means causing harm to property, while trespass means entering someone’s land without permission.

For example, if a group gathers outside a businessman’s shop and breaks windows to protest against high prices, it is an unlawful assembly. Similarly, if five people enter a private farmhouse without permission and refuse to leave, they can be charged under IPC 141.

5. Forcing Someone to Give Up Their Rights

If an assembly uses force to take land, block a road, stop someone from using water, or remove people from a place, it is unlawful. The law protects public and private property from mob violence.

For instance, if a group forces a family to vacate their house by using threats, it is an unlawful assembly. Similarly, if five farmers block a well and prevent others from taking water, they can be punished under IPC 141.

6. Forcing Someone to Do Something Against Their Will

A group that forces a person to do something they are not legally required to do or stops them from doing something legal is unlawful. This protects individual freedom from mob influence.

For example, if a group forces a restaurant owner to close his shop permanently, it is an unlawful assembly. Similarly, if a group prevents a student from attending school, it is also punishable under IPC 141.

7. When a Lawful Assembly Becomes Unlawful

A gathering may start lawfully but can later become unlawful if the members decide to commit an illegal act. The moment the objective changes to violence or intimidation, it becomes an unlawful assembly.

For instance, if a peaceful protest suddenly turns violent, and people start burning public buses, it becomes an unlawful assembly. Similarly, a group meeting for religious discussion is lawful, but if they later attack another community, it becomes unlawful.

8. Minimum Number of People Required

To qualify as an unlawful assembly, there must be at least five people. If there are fewer than five, IPC 141 does not apply, but other sections of the IPC may apply for individual crimes.

For example, if only three people gather and commit violence, they may be charged with assault but not unlawful assembly. However, if five or more people do the same, they can be punished under IPC 141.

9. Role of Common Object in Unlawful Assembly

All members of the assembly must have a common unlawful purpose. Even if some members do not actively participate, but they support the illegal goal, they are guilty under IPC 141.

For instance, if a group gathers to set fire to a shop, all members are guilty even if only one person lights the fire. Similarly, if a mob plans to attack a politician’s house, even those who stand by and encourage the act are punishable.

10. Legal Consequences of Unlawful Assembly

Being part of an unlawful assembly is a criminal offense. The punishment may include arrest, imprisonment, or fines, depending on the severity of the crime. If violence occurs, additional sections like rioting and destruction of property may apply.

For example, if a group unlawfully blocks a highway, they may get a fine. But if they attack the police, they may face imprisonment of up to six months or more.

Example 1: Protest Turning Violent

A group of 10 people gathers in front of a government building to demand higher wages. Initially, the protest is peaceful, but later, some members start throwing stones and damaging property. The entire group is charged under IPC 141 because their common objective turned unlawful.

Example 2: Encroachment on Land

A village dispute arises where five people forcefully enter another person’s farmland and start plowing it, claiming it belongs to them. Since they used force to take possession, this is considered an unlawful assembly under IPC 141.

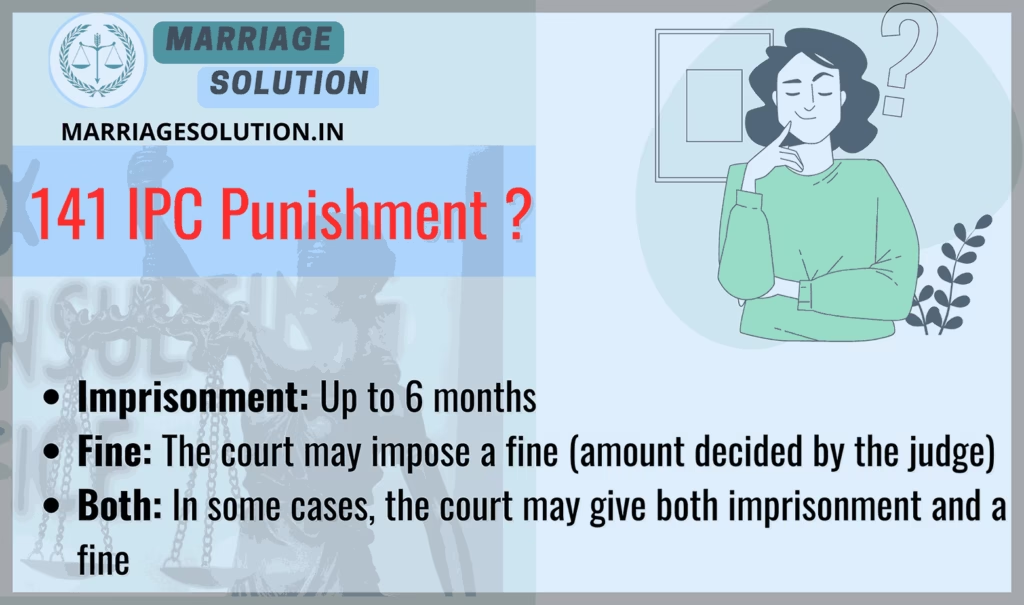

IPC 141 Punishment

Imprisonment: Up to 6 months

Fine: The court may impose a fine (amount decided by the judge)

Both: In some cases, the court may give both imprisonment and a fine

141 IPC bailable or not ?

IPC 141 is a bailable offense. This means that if a person is arrested under this section, they can apply for bail and may be released by the court or police.

Section 141 IPC case laws

1. State of Maharashtra vs. Ramlal (1980)

Case: A group of six people blocked a government office and threatened officials to pass illegal orders in their favor.

Result: The court ruled that the assembly had an unlawful objective and convicted all members under IPC 141.

2. Kishan Lal vs. State of Uttar Pradesh (1995)

Case: A peaceful protest turned violent when protestors attacked police officers and damaged public property.

Result: The court held that the initial gathering was legal, but as soon as violence started, it became an unlawful assembly under IPC 141. The accused were punished with 3 months imprisonment and a fine.

3. State of Tamil Nadu vs. Rajan (2005)

Case: A group of people forcefully occupied private land and refused to vacate, claiming it was theirs.

Result: The court ruled that using criminal force to take possession of land is unlawful under IPC 141. The accused were fined and sentenced to 4 months in jail.

4. Ravi Kumar vs. State of Bihar (2012)

Case: A mob of villagers stopped a government water project by threatening engineers and damaging equipment.

Result: The court found that using criminal force to resist government work made the group an unlawful assembly. The main leaders were sentenced to 5 months imprisonment, while others were fined.

5. Delhi Police vs. Protestors (2020)

Case: A large group of people blocked a highway for days, causing disruption and refusing to leave despite police orders.

Result: The court ruled that blocking public roads in a way that harms public order is unlawful. The protestors were fined but not jailed as there was no criminal force used.

Section 141 IPC in short information

| IPC Section | Offense | Punishment | Bailable/Non-Bailable | Cognizable/Non-Cognizable | Trial By |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPC 141 | Unlawful assembly | Up to 6 months imprisonment, fine, or both | Bailable | Cognizable | Magistrate |

141 IPC FAQs

How many people are required for an unlawful assembly under IPC 141?

At least five or more people must be involved to form an unlawful assembly. If fewer than five, IPC 141 does not apply.

Can a peaceful gathering become an unlawful assembly?

Yes. A gathering may start as peaceful, but if the members decide to use violence, force, or break the law, it becomes unlawful under IPC 141.

What is the punishment for unlawful assembly under IPC 141?

The punishment can be up to 6 months of imprisonment, a fine, or both, depending on the seriousness of the offense.

Is IPC 141 a bailable offense?

Yes, IPC 141 is a bailable offense, meaning the accused can get bail from the court or police.

Is IPC 141 a cognizable offense?

Yes, IPC 141 is a cognizable offense, meaning the police can arrest the accused without prior approval from the court.

If you need support with court proceedings or any other legal matters, don’t hesitate to reach out for assistance.

Court or any other marriage-related issues, our https://marriagesolution.in/lawyer-help-1/ website may prove helpful. By completing our enquiry form and submitting it online, we can provide customized guidance to navigate through the process effectively. Don’t hesitate to contact us for personalized solutions; we are here to assist you whenever necessary!

Right to Information RTI act :Your Comprehensive Guide (Part 1)

The Right to Information (RTI) Act : Explore the essence of the Right to Information (RTI) Act through this symbolic image. The image features legal documents, emphasizing the importance of transparency and accountability in governance. The scales of justice represent…

What is Article 371 of Indian Constitution ?

Article 371 of the Indian Constitution grants special provisions to specific states and regions within India, addressing their unique historical, social, and cultural circumstances. These provisions aim to accommodate diverse needs and protect cultural identities within the constitutional framework.

Indian Labour law : Your Comprehensive Guide (Part 1)

The purpose of labour laws is to safeguard employees and guarantee equitable treatment at the workplace, encompassing aspects such as remuneration, security, and perks. These regulations establish a secure ambiance by imposing minimum wage requirements, ensuring factory safety measures are…

GST :Your Comprehensive Guide (Part 1 – Understanding the Basics)

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) is like a big change in how we pay taxes in India. It started on July 1, 2017, and it’s here to simplify things. Before GST, we had many different taxes, and it could…